Alpenglow: The Solana Upgrade That Rivals NASDAQ

Alpenglow is set to be one of the most significant upgrades to the Solana network yet, but it is a hefty topic.

Why read this article?

Actually simple and clear – no jargon spam

Beautiful diagrams that make sense

Written by someone who struggled just like you

No PhD required

We did everything. Read the whitepaper cover to cover. Watched Brennan Watt's Lightspeed breakdowns (absolute goat). Scrolled through endless Twitter threads. Studied @toghrulmaharram's technical breakdown. Nothing clicked.

So we spent days making notes, sketching diagrams on whiteboards, rewatching videos frame-by-frame, breaking down every concept until it finally made sense.

How to read this guide?

This guide is structured to meet you wherever you are:

- Sections 1-2: The Headlines: what’s broken, why it matters, and what’s changing. Perfect if you just want the big picture.

- Section 3: How Solana Currently Works: deep dive into TowerBFT, Proof of History, and Turbine. Read this if you want to understand what Alpenglow is replacing and where today’s system falls short.

- Section 4: What is Alpenglow: how Votor and Rotor work (new architecture), the 20+20 resilience model, dual-path finality, and why it’s orders of magnitude faster. This forms the technical core of the upgrade.

- Section 5: Timeline & What's Next: when will be Alpenglow shipped and what it changes (multiple Concurrent Leaders preview).

You can stop after Section 2 and walk away informed. Or keep reading to understand one of the most significant blockchain consensus upgrades ever designed.

Core Finality Problem on Solana

TL;DR:

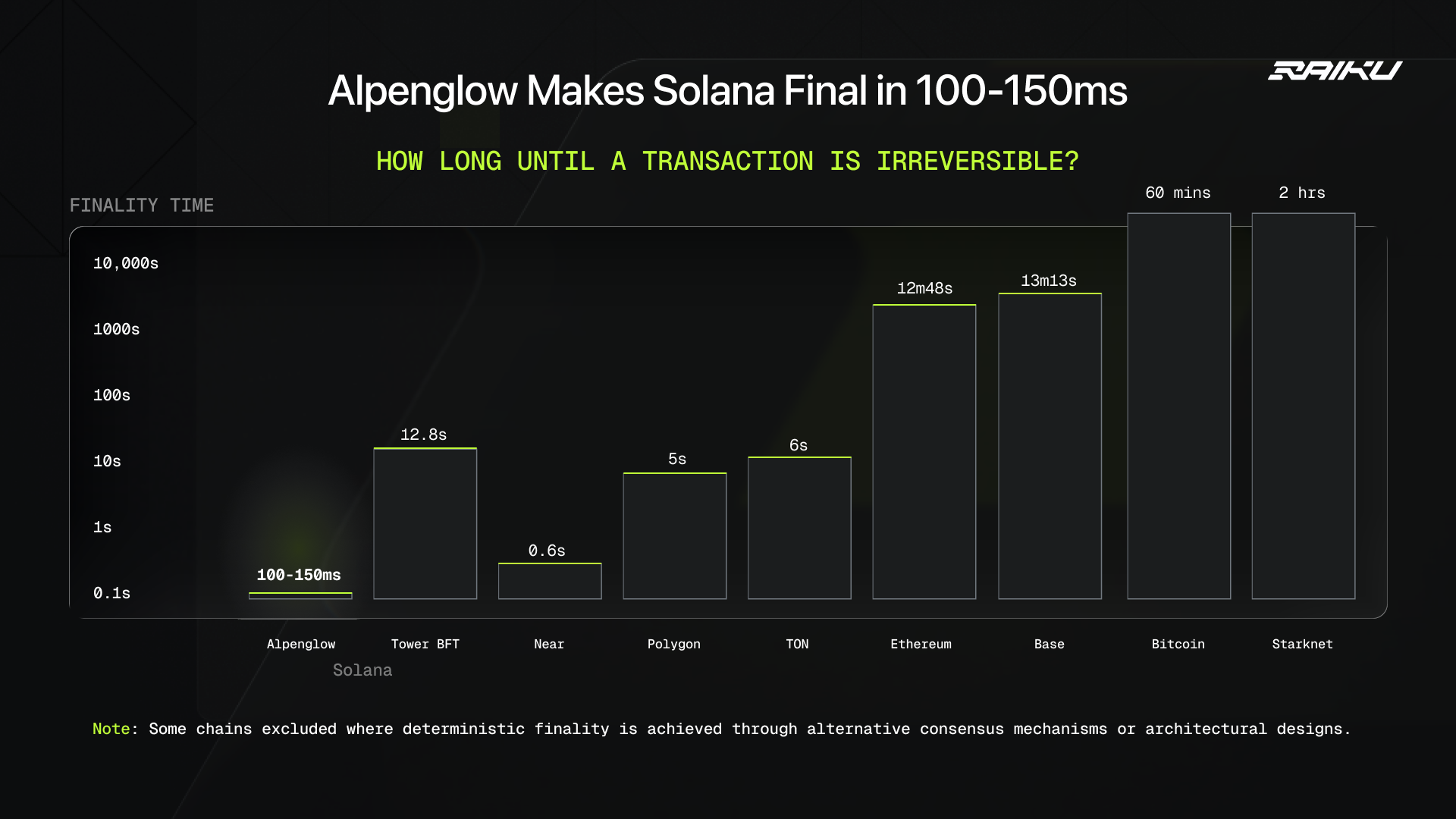

- Current Solana’s true deterministic finality typically takes about 12.8 seconds on mainnet, even though users see optimistic confirmations in ~500–600ms.

- Alpenglow aims to reduce deterministic finality to roughly 100–150 milliseconds (around a 100× reduction in time to finality).

Solana feels instant. Your wallet says "confirmed" in half a second. Apps update immediately. Everything looks perfect. But it's not, at least not yet.

What you see as "confirmed" is just the network's best guess. Exchanges, bridges, and anyone moving serious money? They're waiting for something stronger, proof that the transaction can never be reversed.

And that takes 12.8 seconds.

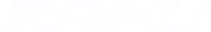

The Two-Finality Problem

Today, Solana has two levels of finality: optimistic and deterministic.

Optimistic finality (as the name suggests) is not really finality, but confirmation which takes around 500ms. When users see “Your transaction is confirmed!”, it means that the network expects that this transaction will land, but it’s still technically reversible.

It’s good enough for showing balances, UI updates, low-stake transactions, but it doesn’t reflect that your transaction is “indeed” confirmed.

The 2nd type of finality is deterministic. It takes around 12.8 seconds and it means that your transaction is indeed confirmed, it becomes cryptographically irreversible.

Unfortunately, this segregation hurts core infrastructure:

Exchanges: Must wait 12.8s before crediting deposits

Bridges: Delay cross-chain transfers waiting for finality

Off-ramps: Can't release fiat until transactions are final

It’s pretty similar to food delivery apps. Imagine you’re ordering some avocados. The app says "Order confirmed!" after 0.5 seconds. But the restaurant waits 12.8 seconds before cooking, "just in case the order gets cancelled." This happens for every order, even though cancellations are basically impossible.

You don’t care about that with Alpenglow: you order food -> order is confirmed -> cooking starts in 100 milliseconds. The process is essentially the same, but it’s much faster: you can get your food faster and the restaurant can process more orders.

What does Alpenglow replace?

Before we dive into Alpenglow, we need to understand what it replaces in current architecture. Solana runs on 3 core systems:

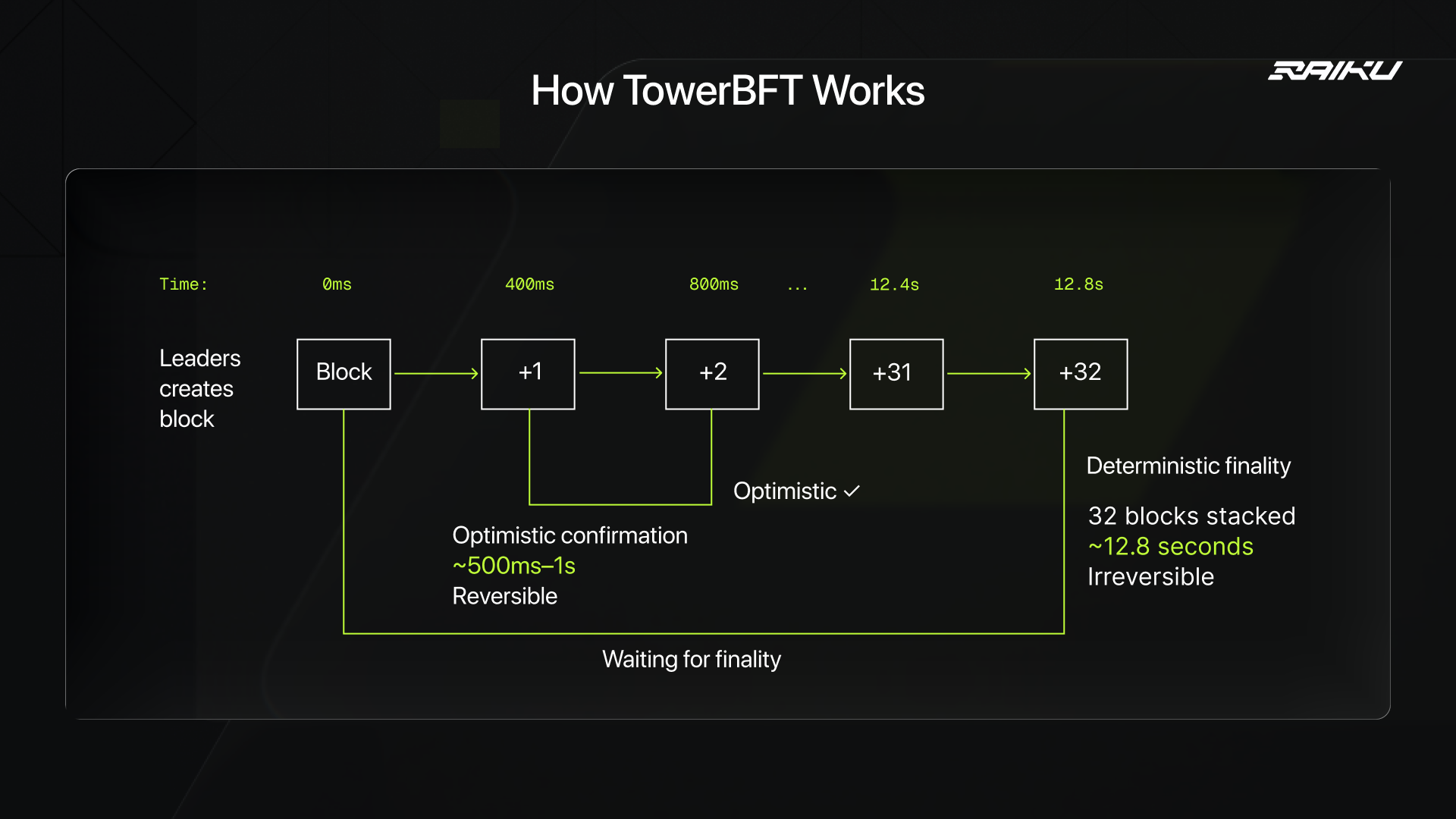

TowerBFT: tracks validator votes over time and decides when a block becomes irreversible. A block only becomes final after a confirmation depth (roughly 32 blocks).It has strong safety, but slow finality (~12.8 seconds)

Turbine: it is the main reason Solana can push huge throughput. It quickly spreads blocks across the network so all validators receive data in parallel instead of one-by-one. This is what enables Solana’s high TPS and low fees.

Proof of History (PoH): creates a verifiable timestamp for everything. Also helps validators know: "Has the current leader taken too long? Should we skip them?" It keeps the chain moving even when leaders are slow.

So what’s the problem here?

Vote transactions eat up to ~75% of block space, validators pay ~$60k/year just to vote, 12.8-second deterministic finality feels slow compared to optimistic finality. The gap is too big.

How Alpenglow approaches this problem

Alpenglow collapses these responsibilities into two simpler components: Votor and Rotor.

Votor replaces TowerBFT and Proof-of-History and combines them into a single component.

Before: TowerBFT requires validators to observe ~32 confirmation slots before considering a block final.

Now: Once enough validators vote "yes," the block is final immediately.

In result, deterministic finality lowers to ~100 milliseconds (prev. 12.8 seconds), vote transactions don’t clutter blocks. For timing, Votor uses simple local timers instead of PoH's continuous computation.

Rotor is replacing the Turbine in the old mechanism. Technically, it does the same job, but uses fewer relay hops and handles error correction better.

In result, blocks reach validators faster (faster coordination) and network issues are handled better.

How exactly do these improvements benefit Solana?

To answer this question, we need to get more technical, but we’ll keep it precise and simple as possible. It’s time to understand how the system works under the hood: TowerBFT's voting mechanism, Proof of History's hash chain, and Turbine's block propagation.

What’s wrong with TowerBFT?

TowerBFT is Solana's current consensus protocol, the system that decides which blocks become part of the permanent ledger and when they're irreversible. It sounds amazing in theory, but in practice it has several drawbacks.

Drawback 1: Fork-Based Consensus

TowerBFT's most distinctive feature is that it operates on forks, not individual blocks. A fork occurs when multiple valid blocks compete for the same slot, creating diverging chains:

Block 1 → Block 2 → Block 3a → Block 4a

→ Block 3b → Block 4b

In this example, both Block 3a and Block 3b extend Block 2, creating two competing forks (Fork A and Fork B respectively). In traditional BFT protocols (like Tendermint), validators vote on blocks one at a time. Block 5 must reach consensus before anyone proposes Block 6.

This creates a clean sequential chain, where each block waits for consensus:

Block 1 → Vote → Finalize → Block 2 → Vote → FinalizeIn TowerBFT, it’s different. Because Solana prioritizes throughput, blocks are produced continuously without waiting for votes. Leaders produce blocks every 400 milliseconds regardless of whether the previous block has been voted on.

This is called continuous pipelining, the block production pipeline never stops (happens in parallel):

Block 1 → Block 2 → Block 3 → Block 4 → ...

↓ ↓ ↓ ↓

Vote Vote Vote Vote

Fun consequence is that you can have multiple valid blocks for the same slot that create temporary forks. Why do they happen?

Well, TowerBFT doesn't wait for consensus before producing the next block. Leaders produce blocks continuously every 400ms, which means:

Network delays: a leader might not see the most recent block and builds on an older parent

Leader handovers: during transitions between 4-slot leader windows, timing issues can create competing blocks

Network partitions: temporary splits cause different validators to see different chains

Malicious behavior: byzantine validators deliberately create competing blocks

Drawback 2: Votes are onchain transactions

Here's where TowerBFT gets unusual: every validator vote is a blockchain transaction. When you vote, you're not sending a private message to other validators. You're creating a transaction that:

Gets sent to the current leader

Gets included in the next block

Becomes part of the permanent ledger

It is a good thing because it’s transparent where voting history is cryptographically proven, but:

These vote transactions consume ~75% of block space

Validators pay fees for voting (~1 SOL/day = $165/day = $60k/year), when they’re supposed to make money. It raises the barrier for new validators to join.

Drawback 3: Vote towers and stacking commitments

When you vote for a fork, you're not just saying "I like this block." You're locking yourself in through exponentially increasing lockouts. Every vote creates a lockout period, a number of slots during which you cannot vote for a competing fork. Each new vote on the same fork makes your previous lockouts double.

Let’s imagine you vote 5 times on Fork A:

Vote #5 for Block #1005: Lockout = 2 slots (recent, easy to change)

Vote #4 for Block #1004: Lockout = 4 slots

Vote #3 for Block #1003: Lockout = 8 slots

Vote #2 for Block #1002: Lockout = 16 slots

Vote #1 for Block #1001: Lockout = 32 slots (old, very expensive to change)

This creates a "tower" of votes, where bottom votes have massive lockouts and top votes have small ones. Why should we care? Well, if new Fork B appears and validators want to switch to it, they'd need to:

Either wait for all their lockouts to expire (could be hundreds of slots)

or break their lockouts (lose rewards, risk slashing)

The deeper your tower, the more economically painful it is to switch. Validators naturally converge on the same fork because switching becomes increasingly expensive.

Drawback 4: Following the heaviest fork

How do validators decide which fork to vote for? They follow the one with the most stake. The process usually looks like this:

Look at all competing forks

Check which validators have voted for each fork

Add up the stake on each fork

Vote for the "heaviest" fork (most total stake)

Only if it doesn't violate your existing lockouts

For example, if Fork A has 70% of stake voting for it and Fork B has 30%, most validators vote for Fork A -> Fork A gets heavier -> Fork B is eventually abandoned.

Over time, the network converges. One fork accumulates so much stake that switching to an alternative becomes economically irrational.

Drawback 5: Two-Level Finality

As we mentioned earlier, Solana has 2 levels of finality — optimistic and deterministic.

When a block gets ≥66% of stake voting for it, it's marked as "confirmed”, which is an optimistic finality. At this point, the block is probably final. In Solana's entire history, no optimistically confirmed block has ever been reversed.

Block is first created, then spread via turbine, validators vote for it -> 500ms in total.

For deterministic finality (absolute mathematical certainty) you need the block to be 32 blocks deep. Why 32? Because of exponential lockouts.After 32 votes stacked on top of a block:

The oldest votes have lockouts of 1024+ slots

Breaking these lockouts would cost validators massive rewards

Economically impossible to reverse

32 blocks × 400ms per block = 12,800ms = 12.8 seconds

Only at this depth does the block become "rooted" (finalized) and removed from validators' vote towers. The problem is that users see "confirmed" in half a second. But exchanges wait for "finalized" at 12.8 seconds. This 12-second gap is what Alpenglow eliminates.

What’s wrong with Proof-of-History?

PoH is Solana's timing mechanism, proving time has passed without synchronized clocks.

Leader hashes data with SHA-256, then hashes that output, repeating 12,500 times per block.

SHA-256 speed is fixed. 12,500 sequential hashes = ~400ms of computation. It's a cryptographic stopwatch.

Leaders mix transactions into the hash chain, creating timestamps: "Transaction A happened before Transaction B."

In reality, PoH tells the next leader when to skip a slow/offline leader. There can be situations where the validator waits for a block, but nothing arrives their way. The validator has no idea if the leader is offline or the block is just delayed.

With Proof-Of-History, the validator can count hashes. For example, leader should be at Hash #50,000 by the time some block arrives. If it doesn’t, the validator can skip them, so the chain keeps moving when leaders fail.

So that seems like a good mechanism (which is indeed a good mechanism), but it’s not the best. What are the drawbacks?

Validators can just vote without waiting forever. If 60% say "we waited 400ms, nothing arrived," then the leader can be skipped.

12,500 hashes per block is wasted while building transactions. All validators verify every hash, which is inefficient.

PoH doesn’t have real Verifiable Delay Functions (VDFs). True VDFs have succinct proofs, while PoH requires checking all 12,500 hashes, no shortcut.

PoH adds complexity without essential security. Safety comes from voting, not hashes. Simple timeouts work better.

What’s wrong with Turbine?

Turbine is how blocks spread across Solana's validator network without creating a leader bottleneck. If a leader sends a block directly to 1,500 validators, bandwidth becomes the constraint. Turbine breaks blocks into shreds and uses validators to help distribute them.

Here is how Turbine works:

Erasure coding: Leader splits each block into 32 data shreds, then generates 32 coding shreds. Total: 64 shreds. Any 32 can reconstruct the full block.

Tree distribution: Validators organize into layers. The leader sends shreds to Layer 1, who forwards to Layer 2, and so on. Blocks reach the network in 3-4 hops instead of 1,500 direct sends.

Stake-weighted placement: Higher-stake validators sit closer to the root, receiving data earlier.

Dynamic rotation: Tree structure changes per shred to prevent targeted attacks.

However, the model isn’t perfect:

Multi-layer overhead: Each hop adds latency.

Relay failure cascades: If L1 relay fails, everyone downstream loses data.

Complexity: Dynamic rotation, stake-weighted shuffling, and multi-layer coordination are hard to implement and reason about.

The core function, spread blocks fast, can be done more simply. Solana has processed over many billion transactions with this stack. But these systems have fundamental limitations: slow finality, expensive voting, computational overhead, and complexity that makes formal proofs difficult.

Alpenglow fixes all of this.

What exactly is Alpenglow?

Alpenglow is Solana's most significant protocol upgrade ever. The headline result: blocks finalize in ~100-150 milliseconds instead of 12.8 seconds.

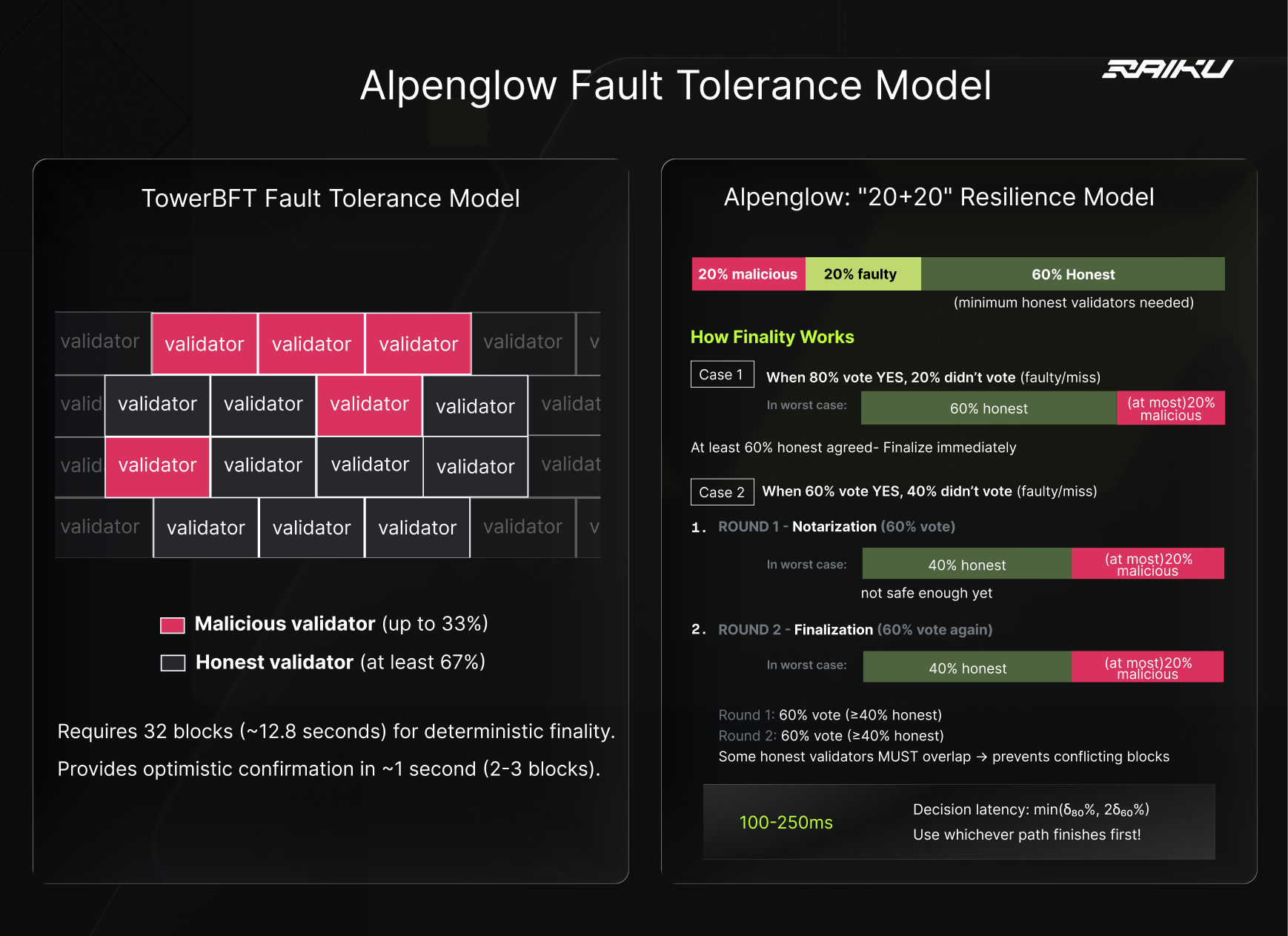

Traditional Byzantine fault tolerance assumes up to 33% of validators might be malicious. This forces protocols to use multiple confirmation rounds and long waiting periods.

Alpenglow takes a different approach: n ≥ 3f + 2p + 1. It means that Alpenglow tolerates up to 20% Byzantine (malicious) validators and 20% crash-faulty (offline/broken) validators. So in total, 40% faulty under good network conditions (minority).

Does this trade-off make any sense?

Controlling 20% of Solana's stake would cost billions of dollars. With slashing mechanisms in place, this is economically irrational. Meanwhile, most real-world failures aren't coordinated attacks, they're nodes crashing, network issues, and software bugs.

Alpenglow optimizes for reality rather than theoretical worst cases.

Dual-Path Finality System

Alpenglow runs two finalization paths simultaneously and uses whichever completes first — fast path and slow path.

Fast path: when 80% of stake votes for a block in a single round, it finalizes immediately. With at most 20% malicious stake, 80% voting YES means at minimum 60% honest validators agreed. Two conflicting blocks cannot both reach 80%, there isn't enough stake available.

Time: ~100-150ms (network latency for votes to propagate)

Slow Path: If 80% doesn't arrive fast enough, validators are geographically distant, some are offline, the network is slow, a backup mechanism kicks in.

A block that receives:

60% stake in first round (notarization)

60% stake in second round (finalization)

...becomes final. The overlap between rounds guarantees honest participation.

Time: ~150 (two rounds of voting).

Both paths run concurrently (at once), Alpenglow doesn't pick a path ahead of time. If 60% of Solana's stake sits in European data centers with excellent connectivity and the remaining 40% is globally distributed or partially offline, the system would look like this:

Slow path: Two fast rounds among 60% European validators = ~150ms

Fast path: One round waiting for 80% global participation = ~200ms+

Decision latency: min(δ₈₀%, 2δ₆₀%)

The slow path finishes first, even though it requires an extra round. This is called optimistic responsiveness: finality latency depends on real message delays, not predetermined timeouts. When the network is fast, finality is fast.

Two conflicting blocks cannot both finalize unless ≥20% of stake acts maliciously, and this would be:

Provably on-chain (cryptographic evidence)

Economically catastrophic (billions lost to slashing)

What exactly is Votor?

Votor replaces TowerBFT and Proof of History. It's the system that decides when blocks are final. It runs two finalization paths simultaneously and uses whichever completes first. The biggest change is where the votes go:

TowerBFT: Every validator vote is a transaction that goes onchain. These consume ~375 KB per block, roughly 75% of block space.

Votor: Validators broadcast votes as lightweight messages via gossip protocol. These votes get aggregated into certificates using BLS signatures.

A certificate is a compact proof that quorum was reached consisting of aggregated signature and metadata about the vote, ~400 bytes in total.

In result, consensus overhead is reduced by 99.9% (375 KB → 400 bytes)

Votor uses five types of votes. Each serves a specific purpose.

Notarization Vote: Cast when a validator receives and validates a block. This is the primary vote that counts toward the 60% (notarization) or 80% (fast-finalization) thresholds.

Skip Vote: Cast when the timeout expires without receiving a valid block. Prevents the network from stalling when leaders go offline.

Notarization-Fallback Vote: When a validator sees 40% already voted for a block, no other block can reach 80% (only 60% stake remains). It's safe to support the winning block even if the validator initially voted to skip.

Skip-Fallback Vote: When the leading block only has 30% support and votes are scattered across other options, no block can reach 80%. It's safe to skip the slot entirely.

Finalization Vote: After a block gets a 60% Notarization Certificate, validators who voted for it cast finalization votes. When 60% finalize, the block is deterministically final.

Votes aggregate into certificates when thresholds are reached:

Votes aggregate into certificates when thresholds are reached:

Notarization Certificate (60% notarization votes) → Block is locked

Fast-Finalization Certificate (80% notarization votes) → Block is final (1 round)

Notar-Fallback Certificate (60% mixed votes) → Block is locked

Skip Certificate (60% skip votes) → Slot is skipped

Finalization Certificate (60% finalization votes + Notarization Cert) → Block is final (2 rounds)

The key components of Votor are the pool and timeouts. Pool is a local data structure that collects votes, detects thresholds, generates certificates, and broadcasts them. Timeouts replace PoH hashing with local timers. If no block arrives within 400ms, the validator casts a skip vote. If 60% skip, the slot is skipped.

What exactly is Rotor?

Rotor is the system that spreads blocks across the validator network. The biggest change is the structure: single-hop relay instead of multi-layer tree.

With Turbine (classic version), validators relay shreds through 3-4 layers. Complex tree structure with stake-weighted positioning.

With Rotor (Alpenglow), the leader assigns each shred to one relay validator. Relays broadcast directly to all validators. One hop.

Leader breaks each block slice into 64 shreds using Reed-Solomon erasure coding — 32 data shreds and 32 coding shreds. Validators need any 32 of the 64 to reconstruct the slice, Rotor can tolerate up to 32 failed or malicious relays.

Leader assigns shreds to relay validators (stake-weighted). Each relay broadcasts their shred to everyone. Validators collect shreds and reconstruct blocks in Blokstor.

This brings multiple key improvements:

Simpler: Single hop vs multi-layer tree. No complex routing.

Better fault tolerance: 50% of relays can fail and blocks still propagate.

Stake-weighted bandwidth: Relays proportional to stake, aligning with rewards.

Fast: Latency between δ and 2δ (one to two network delays). Approaches physical network limits.

Timeline & What's Next

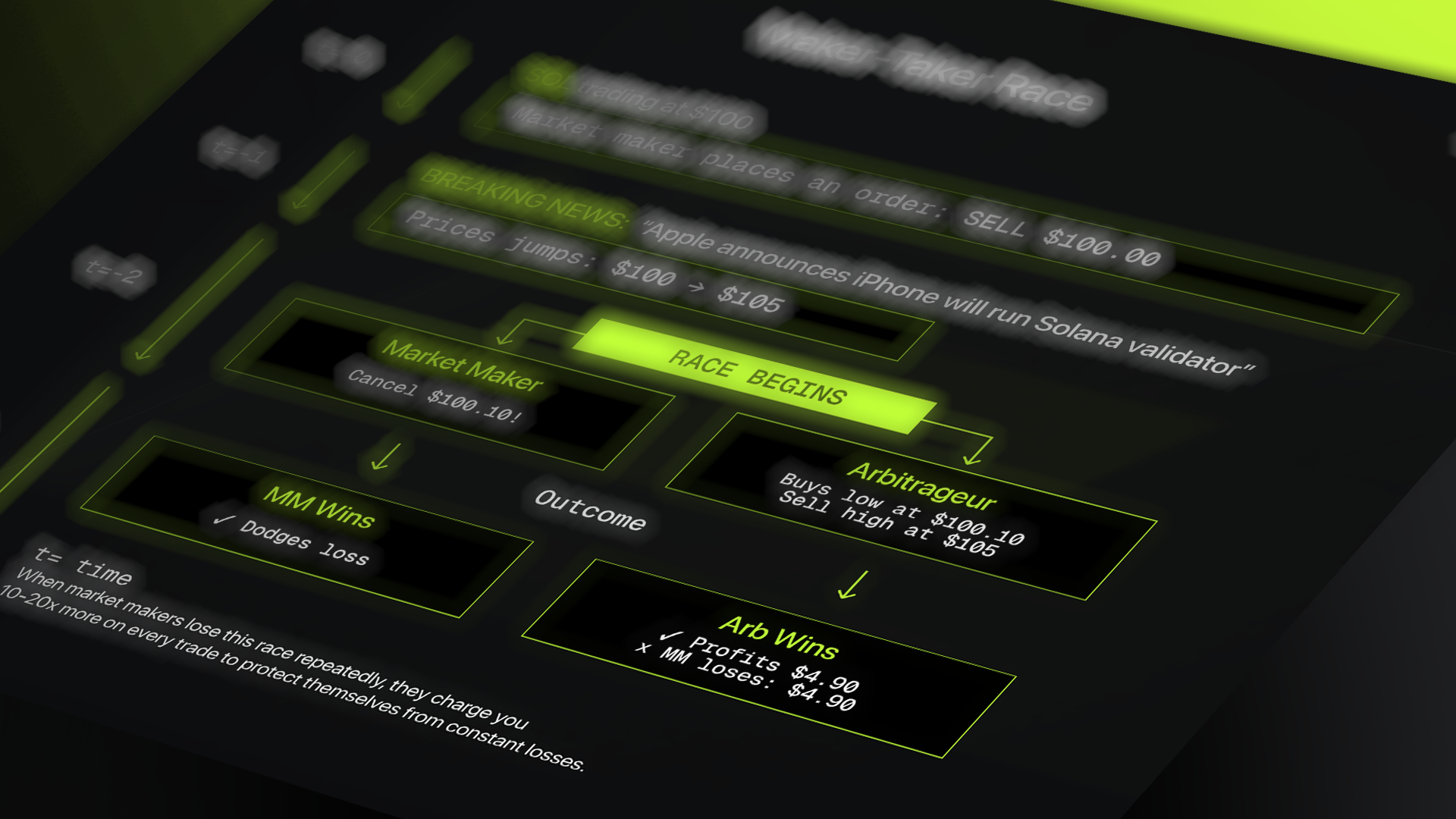

Alpenglow is running locally at Anza today. The target is early 2026 mainnet deployment.

Beyond faster finality, Alpenglow unlocks Multiple Concurrent Leaders (MCL), allowing multiple validators to produce blocks simultaneously instead of one leader controlling ordering for 1.6 seconds.

This creates a competitive marketplace that makes censorship and MEV manipulation significantly harder. MCL represents a fundamental shift in how Solana handles block production and transaction ordering, we'll dive deep into this in the next article.